Although this question is part of a long-standing debate in copyright law circles, I’ve picked up on this issue in light of recent comments emerging from the Obama administration, specifically by the current Vice President, Biden that “Piracy is flat, unadulterated theft“, and that “it should be dealt with accordingly.”

It is perhaps important to contextualise his statement in light of two specific events that I find particularly relevant:

1. The recent ‘Joint Strategic Plan to Combat Intellectual Property Theft’ statement delivered by the White House a few months ago (note the use of the word ‘theft’ in the title itself).

2. The ACTA negotiations, spearheaded by the US government, which while being masqueraded as a ‘trade agreement’ is in fact an intellectual property rights treaty designed to combat piracy.

WHY DISTINGUISH BETWEEN THE TWO?

Widespread public resentment surrounding the negotiation tactics as well as the subject matter of ACTA has been well documented, and frankly, heartening to watch, but I feel a need to stress on the importance of distinguishing ‘copyright infringement‘ from ‘theft’ to prevent any equivocation on the part of government authorities to sway public opinion. Although the debate appears to be restricted to American circles for now, I believe that Indian policy must not be influenced by such misnomers on the issue of combating piracy and general copyright infringement policy debates in the future, besides the fact that it has significant jurisprudential ramifications.

LEGAL BASIS FOR THE PROP THAT COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT IS NOT THEFT

DOWLING AND GROKSTER CASE LAW

In the case of Dowling v. United States (1958) the US Supreme Court concluded that the National Stolen Property Act did not extent to items which infringed copyright. In this case, Paul Dowling was invested in the business of selling bootleg recordings of Elvis Presley, but the court in pertinent part observed that:

“The infringer of a copyright does not assume physical control over the copyright nor wholly deprive its owner of its use. Infringement implicates a more complex set of property interests than does run-of-the-mill theft, conversion, or fraud.”

Some have argued that the observation in the more recent case of MGM v. Grokster (2005) that “deliberate unlawful copying is no less an unlawful taking of property than garden-variety theft” discount the very argument. However, the basic legal difference between copyright infringement and theft is in no way negated by this observation.

NATURE OF RIGHTS

Perhaps the essence of the difference is in the nature of property rights itself, something that deserves closer jurisprudential analysis, which I will conveniently exclude from this post. However, I, like several others, argue that copyright infringement is not theft simply because one deprives its owner of its use completely, while in the case of infringement, there is no such deprivation. This flows from the ‘nature of rights’ issue, wherein copyright being a government granted monopoly right can continue to be exercised by the copyright/monopoly holder in spite of infringement, while in the case of, for example, theft of a watch, one is deprived of the ability to read time, sell or rent out the watch.

A similar argument has been advanced on the issue of music file-sharing, and I strongly agree with the view that merely because a particular song has been downloaded illegally, it does not directly account for a lost sale and therefore revenue loss to the recording label. Such a position presupposes that if that song has not been pirated, it would have resulted in a legal purchase of the same track by the individual, which is an incongruous presumption. No wonder the losses claimed by the entertainment industry have been dismissed as grossly inflated and inaccurate. Infringement of that track does not prevent future sale of the same track, so it is really correct to call it ‘theft’?

LEGAL TERMINOLOGY v. COLLOQUIAL LANGUAGE

This argument has been used to support the view that ultimately, actual legal terminology is unimportant, and if they are used interchangeably in the colloquial sense, then its use in any debate is perfectly understandable. Terry Hart in his blog argues that emphasising on the legal meaning of words ‘accomplishes little more than arguing for the sake of argument,’ and others argue that eventually, it is a sense of perception and feeling – people will be better able to understand the meaning of copyright infringement by equating the calling it ‘content theft’.

However, as I stated in the introductory paragraph, the very problem is that in using colloquial terms, by disregarding their legal meanings and implications, it is possible that the masses will be presented with a particularly grim view of infringement. The term ‘theft’ carries with it significant ethical connotations, is regarded as moral turpitude, and involves considerable value-judgement. While this may not seem as much to many, from a public policy angle and certainly a legalistic approach, such equation is simply preposterous.

I’ve noticed some specific cases where copyright infringement is presented as theft and while in some cases it is understandable, in others it is just not.

1. Content Creators: Equating copyright infringement with theft for a content creator arguably stems from emotional considerations – the feeling that they are being deprived of something that belongs exclusively to them. To some extent, their anguish is understandable, given the serious impact infringement has on creators directly. But equating the two is simply ignoring the real problem and preventing viable solutions to tackle the problem from being found.

2. Anti-piracy groups: The biggest culprits on this point are anti-piracy groups who have an obvious interest in equating the two (see above on inflated revenue loss figures) Backed by political groups and vice versa, their propaganda efforts have continued on and on. Remember the original DVDs we bought with the anti-piracy clip and voice-over saying:

“You wouldn’t steal a car. You wouldn’t steal a handbag. You wouldn’t steal a mobile phone. You wouldn’t steal a DVD. Downloading pirated films is stealing. Stealing Is Against The Law… Piracy: It’s a crime.”

Fortunately, their propaganda efforts have been criticised by most people and have been the butt of several jokes. However, this does not mean that their ads/campaigns/statements will have no effect whatsoever on the common man. Some people are easily brainwashed, indifferent or just too lazy to process the information and decide for themselves. So there is always a danger that in the minds of an average man, copyright infringement is in fact, theft.

3. Educational information: I have noticed that in order to discourage infringement of copyright, it has often been equated with theft, perhaps to increase stigma attached to the act. But surely there are other ways to discourage an unwanted act than by equating two legally distinct crimes. Do we really need to equate two different crimes just to make the common man understand the implications better because there exists a possible analogy?

Again, I reiterate that it is a not a mere semantic issue. If piracy is to be tackled effectively, in India or elsewhere, creators, anti-piracy groups and politicians must understand that infringement and theft are conceptually, legally and in terms of socio-economic effects, completely different from one another. Combating the two require distinct processes, and only when the difference in the two is properly appreciated and presented to the public can policy formulation effectively take place.

Thus, it is my humble opinion that simply put, copyright is not a property right; it is not a right of ownership of property in the ordinary sense; it is a privilege, and it is certainly not absolute. For this and the reasons above, I find that copyright infringement is not theft and engaging in a rhetoric that equates the two, deeply damages the possibility of understanding the problem of infringement and finding suitable solutions to it.

enjoyed the post Amlan! fantastic.

Interesting post, Amlan!…and i agree with you completely on the point that copyright is not property and it is not a right of ownership of property ..it is intellectual property and a right of ownership (and exploitation)of intellectual property

However, don’t you think you should also have addressed the ‘value’ concept in your arguments…because when someone uses/exploits a copyright protected work without paying the due royalty/amount for it….the owner of the copyright in the work is losing revenue that should rightfully have been his…and as far as entertainment industry example goes…true infringement does not prevent future sales of the track..but availability of cheaper/no cost(free) versions do greatly impact no. of buyers of original track from the owner of copyright …..

It is undisputed that piracy causes depreciation in value of the work…and I for one think if that depreciation is 100%….it might not be a theft in the semantic sense but it most certainly amounts to ‘robbing ‘ one’s work of its complete and whole value….so piracy and theft might have more in common than an ‘analogy’ relation…maybe piracy is ‘theft’ of ‘intellectual property’..

Note: robbing has not been used in literal or legal sense

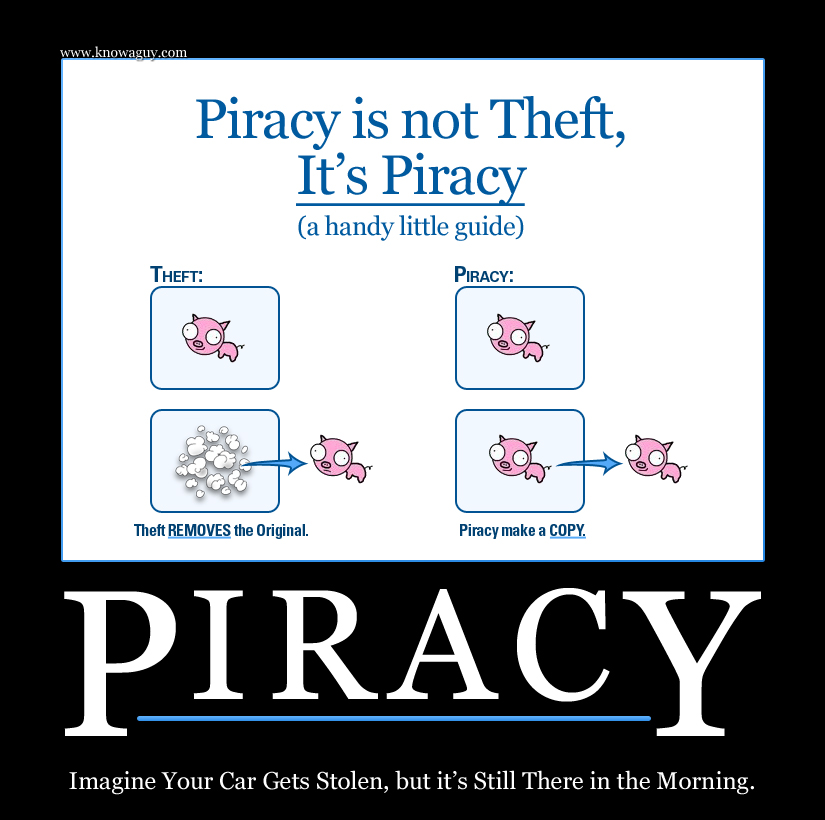

….( I believe the pictorial representation discussed the physical aspect of property and how in case of piracy it is just a copy being made..i disagree slightly over here..intellectual property is not in the physical realm..i.e it is intangible..so on making an unauthorised copy, the copyright owner is certainly being deprived of his right to make a ‘copy’ which technically comprises one of the rights constituting the bundle of rights called copyright…)

So what I found, I guess, in this post and also from a (semi)private conversation with Amlan 😉 was, well, just that. IPR are not by “natural given rights” in the way one might consider physical property a right given by nature (although I personally find this questionable – all the rights we grant ourselves in society are just conventions that make it easier for us to co-exist with our fellow human beings: nature doesn’t really grant us any rights at all, which goes to show when it comes to, say, territorial struggles or a lack of civil rights awareness in societies with very strict social control).

Being from a political party, and with a slightly ideological view of the matter, I obviously do not believe in the notion of infringement at all: copyright is virtually dead, at least in societies with very high internet access penetration. Considering the easy with which one can replicate physical media (like DVDs or CDs) it is also questionable whether copyright exists in any meaningful way in the physical media distribution monopolies (even the technological protection methods, which in theory could replace copyright by introducing a contract law element in the distribution monopolies, are usually hacked or cracked shortly after their release – the exception being PS3 which was not jailbreaked until a few months ago, thereby also rendering the technological protection for their online leasing service quite useless).

Perhaps legally as well as economically we would all be happier if we searched for a system that was not rights-based at all, whether those rights are natural, granted or awarded. In any case, it would be interesting to hear what lawyers specialised in RIGHTS feel about such an approach.

Hey Amlan,

This is great stuff. It’s nice to see some deeper thought into issues such as the concept of IP as property.

However, I’d like to offer some push-backs and comments to some of your statements, for the sake of discussion on this.

Firstly, though it balances more on a semantics difference than a conceptual one, I’m wondering why you haven’t attacked the word ‘piracy’ either, as opposed to the more ‘correct’ and less-value-loaded term ‘infringement’.

More of a minor critique, which I hope you don’t mind. I just thought that you might appreciate it since you seem interested in writing on these topics. – You call a copyright a government granted monopoly right. Technically, it is not a ‘monopoly’ right – but an exclusion right. The word ‘monopoly’ is an economically loaded term, the right to which isn’t quite what is granted to copyright owners – regardless of how often the two may overlap in reality.

Moving on to your point about ‘content creators’. Here, firstly, I’d ask if you could explain more about what you mean when you say infringement affects content creators directly.

Secondly, it’s more than an emotional consideration, but rather a more moral consideration that the creators of content are owed something by the society which gains or makes use of their creation – which also happens to be one of the main kernels of Locke’s theory of property. Judging how much this ‘something’ that is owed, is another discussion altogether – but one important factor in deciding that is keeping in mind the following: that this still doesn’t not necessarily make infringement a ‘bad’ thing. Any decent theory of IP tells us that IP is essentially trade-offs – and here too – tradeoffs ‘can’ justify an extremely low priced or possibly even free creation. (ie, hypothetically if the primary preference of the state were to increase the size of the ‘commons’…)

Finally, I’d like to know more about what you mean when you say that copyrights are a privilege. How do you mean privilege and how exactly are copyrights a privilege.

Sorry if you’ve already gone through this in some of the other comments. I haven’t really had time to read them – have just been skimming. If it happens that you’ve already dealt with any of this in the post, or in a comment, do direct me to them.

Best,

Swaraj

Hi Intriguing post….not so when you have a stake in the matter…I find your arguments rather radical.

In your entire post as well as the comments you have received i find it ludicrous that you would attempt to relegate piracy to a position lesser in degree than theft.

I can understand the esoteric arguments on the difference between Infringement and theft. However an attempt to lessen the criminal element behind piracy is nothing short of lets say misguided judgment. For instance Copyright law is the only law among IP Laws to provide for penal action in case of infringement. Also the IT act provides for additional penal action.

Further on your comment that it would be better to come up with a better business model, its been ten years since napster, how come no one has even thought of a solution.

Problem is and problem will be that people have become accustomed to pirating things of the net. In breaching certain boundaries I’d dare to suggest that a search and seizure of computers in several campuses ( law and otherwise) will reveal the extent to which piracy has invaded common life.

Every time enforcement lacks strength it is not right to claim ‘no regulation’ as the way forward.

Of course to understand my stance you would have to work with the normal people working behind the scenes.

In short although pirating is not theft it is much much more.

Amlan,

At the risk of sounding repetitive, excellent post 🙂

I have two comments.

First, on the substance of the post – I do not agree that piracy and theft are conceptually different. Legalistically, yes, there is a difference. Even Section 378 IPC defines theft as taking moveable property out of the possession of another. Theft is an offence against possession (and not ownership, as is commonly misunderstood), while piracy is a violation of other rights in relation to property (again not ownership), but not of possession. But how is there a difference conceptually? Take the example of immovable property where even if I take it out of your possession, it is not theft as the land still exists (and more importantly, theft applies only to movable property). But conceptually, if I dispossess you, is it different from stealing your car? What I mean to say is that the nature of a person’s rights in intellectual property is different from the nature of rights in moveable property, as it is different in immovable property. While legalistically we do not call dispossession in relation to immovable property as theft, it is still conceptually similar to theft. I agree that the difference is necessary in law in order to achieve clarity as to what rights are being denied or illegally trampled upon, but conceptually, why is it different?

Second, in relation to the necessity for a lay person to understand this difference. Why is the difference so relevant? Does it matter if a lay person is told that if someone takes away your land, it is ‘theft’? Or that if you download illegally, it is ‘theft’? Does the semantic difference in law really make a difference to a lay person? This again flows from my first point that I feel at a basic and conceptual level, they are largely the same. Essentially, could you elaborate on this: “copyright infringement is not theft and engaging in a rhetoric that equates the two, deeply damages the possibility of understanding the problem of infringement and finding suitable solutions to it”

Thanks.

Adithya.

@ Anonymous (10:07 pm)

Sorry for the delayed response! Your comment somehow didn’t show up in my inbox. I think you make 4 main points and I’ve tried to address them separately. I’ve taken the liberty of extracting bits of your comment and putting them in quotes while responding.

1) I agree with you completely that the ‘value’ aspect of intellectual property and the impact infringement may have on such value is significant, and perhaps I failed to address that in my post. However, when you say that upon infringement, [i]”the owner of the copyright in the work is losing revenue that should rightfully have been his”[/i], I can agree with you only to a limited extent. Let me give you an example of what I am talking about.

Let’s say I just bought a DVD of the new movie ‘Pirates of the Caribbean’ (excuse the pun 🙂 ) . For whatever reason, I am unable to make a copy of the DVD on my computer. What do I do then? I head over to google, search for a torrent of the movie and download it. Mind you, my DVD is original and a legal purchase. My download thereafter, constitutes copyright infringement. But didn’t the owner of the work get the revenue [i]”that is rightfully his”[/i]? He is entitled to receive, in my opinion, the revenue from the one purchase, and he did receive that revenue. You will agree that I am legally entitled to make a copy of the movie or audio cd as the case may be. And if denied this right, my infringement does not deny him any revenue which should have gone to him.

2) On your second point on the value aspect – [i]”availability of cheaper/no cost(free) versions do greatly impact no. of buyers of original track from the owner of copyright”[/i], – while this is certainly true, one has to also keep in mind that the effect of mass distrubution arising out of infringement works in the opposite direction as well. It increases popularity of the work/song/movie, thereby leading to more potential sales. In a sample of 10, who would never have heard of a song if it wasn’t available of for free, maybe 2 or 3 might actually go and make a legal purchase of the same song, and if not that, then atleast the next album from the same band/next version of the software/sequel to the movie. There is definitely a negative impact on the market of the work, but it is unfair to say that it is all negative.

3) It is for this reason that I do not think one could ever state that there is a net [i]”100% depreciation”[/i], making theft and infringement the same thing. On the other hand, there is absolutely no positive impact arising out of theft of a good and therein lies the difference.

4) On your last point about the graphic, I think I’ve adressed it in the post itself. I do not disagree that on infringement, [i]”the copyright owner is being deprived of his right to make a ‘copy’, which technically comprises one of the rights constituting the bundle of rights called copyright”[/i], but isn’t that why we have a seprate provision for ‘copyright infringement’ under the Indian Copyright Act? I did not say it is not an offence. My point simply is that it is an offence legally distinct from ‘theft.

I hope that answers your questions. I’d like to hear from you on what you make of my responses.

Regards,

Amlan

@ faceless_facetiae

Thanks 🙂

On your first point, I will just like to keep it brief by saying that at the very beginning, it depends on your notion of whether intellectual property actually

constitutes ‘property’ or not. In my opinion, you can consider theft

and infringement to be either conceptually similar or different based on your interpretation of the historical treatment of intellectual property, espeacially in terms of it being an intangible

property right. So I guess we can beg to differ on that point.

As for your second point, I’d like to just highlight a few potential

difficulties in obliterating the legal difference between theft and

infringement.

a) Content creators may be derived from the masses at some point,

given that any individual, at any point of time, without any necssary

expertise or pre-planning, may create a copyrightable work. To present an inaccurate picture would be to mislead them about their rights and thereby create unnecessary hostility towards copyright infringement from content creators, which sadly, seems to be the case at the

moment.

b) The biggest problem is in respect of policy formulation. Take for example the music industry claiming incredible losses due to infringement. If one were to analyse the problem to find solutions, one has to understand the difference between theft and infringement. Maybe if the American government understood this difference, they would not be supporting the recording industry’s view that it leads to

lost sales and trying to combat it from such a viewpoint. Instead if

the government and the masses understood the difference in economic effects of theft vis. a vis. infringement, they would be better able to understand the problem and tackle the problem.

And how does policy formulation relate to the masses? Ideally

at least, policy decisions should be based on accurate information

being presented to the public and with consensus between public and

government alike. So if the right policy is to be determined, even a layman, as you put it, must understand the issue correctly.

Let me illustrate this by means of a rather incredible hypothetical:

Let’s say A.R. Rahman just finished composing the CWG anthem and recorded only a single copy to show to the Organising Committee of the CWG (lets assume no other copy exists). I manage to sneak into his studio.

Infringement – I go into the studio with my laptop, take the CD with the track he just composed, copy them without permission onto my laptop and then leave the CD in the studio itself. Rahman has lost

nothing, so to speak.

Theft – I go into the studio, steal the CD and never return. Rahman has no copy of the song and has lost all revenue arising from sale of the track.

If the government then says they want to spend X amount of money on

retrieving the CD, so that the CD can be released on time, and on

prosecuting the thief, I will fully back them. But if they tell me they want to spend X amount, finding out who currently has the

unauthorised copy of the original songs, finding out which of his

friends he distributed it to, when Rahman has not lost out on any

revenue as such, I may not be agreeable.

Problem in theft – Loss of revenue to Rahman

Problem in infringement – Potential loss of revenue to Rahman based on whether the infringer would have actually bought the songs legally or

not.

Solution to theft – Retrieve the stolen good. Put the original owner

back in possession. Prosecute the offender.

Solution to infringement – Don’t waste money prosecuting infringers

when clearly it has not worked to date. Embrace the digital

revolution; evolve new business methods to tackle the problem.

Thus, “copyright infringement is not theft and engaging in a rhetoric that equates the two, deeply damages the possibility of understanding the problem of infringement and finding suitable solutions to it”

While you may not agree with my problem/solutions, I hope that answers your questions to some degree.

Regards,

Amlan

@ Stenskott

I agree with what you are saying. More than agree though, I am glad that your comment depicts a more realistic picture of the state of copyright as it exists today. When people assert that infringement and theft are the same, in my opinion, they ignore the impact that the internet generally and the online distribution model has had on copyright. The ability to make perfect digital copies of a file and distribute them at ease changes things drastically. Does/should this make infringement on par with theft? Certainly not. Merely because industry associations claim severe losses with the advent of the internet, I think it is unfair to lump two legally distinct offences togther.

I guess the argument is ‘Why should content creators/industry change their model instead of users ceasing to engage in such activity’?. Essentially, on whom does the burden to change lie? For me, it comes down to a question of numbers. Being in denial doesn’t help the industry cause and neither does aggressive prosecution of infringers. They need to evolve systems that accomodate the changes copyright law has witnessed since the internet became mainstream and easily accessible.

Regards,

Amlan

@ Jacob

Thank you for your comment.

I think your comment calls for a disclaimer – I do not condone piracy in any way, nor am I trying to justify it. My point simply is that theft and infringement are different and must be dealt with differently.

Most of what I say comes from my belief that various industry associations must change their tactics in battling infringement. I do not agree with the way in which they are going about tackling the issue and I think a lot of it has to do with the distinction being conveniently overlooked.

I do not dispute that there may be criminal penalties attached to infringement, but there are also civil remedies available under the Act. The difference is not esoteric, but very obviously legal.

On your point about evolving new models to fight piracy – you say that no solutions have been found since Napster. I wholeheartedly beg to differ. I think iTunes in itself may be seen as a wonderful ‘solution’. Like I stated in my comment to stenskott, the effects of piracy have been multiplied with the advent of the internet and online distribution. Prior to iTunes, there was no legal method to procure a digital copy of a song you liked. Infringement was the only option. iTunes and other online music stores have considerably reduced the urge to infringe by providing an easy and perfectly legal solution to the problem.

I hope you see my point and more so because you seem to be asserting that the problem is widespread in India and the ‘people behind the scenes’ know the real impact. But don’t you think if people in India had an easy, cheap and fast way of downloading songs/movies etc., there may not be such a problem in the first place? I know several people who are FORCED to download songs illegally because buying a legal copy of the same is impossible.

This is not the only solution. Movie producers have realised that releasing their movie on torrents for free increases popularity instead of hurting their business (see http://bit.ly/95YWPG). Rock bands such as Radiohead and several Indian bands have also realised this and have evolved business methods wherein their primary revenue comes from concert tickets sales and merchandising.

Every problem has a solution. It’s identifying the problem correctly which is the hardest part, and in my opinion, the first step in finding a solution itself.

Regards,

Amlan

Great post! A really cool topic to discuss.

Probably an example of a ‘painting’ describes the relevance particularly well.. especially after seeing it in a variety of hollywood flicks.

Theft: The culprit breaks in and takes away the painting.

Infringement/ piracy: The culprit makes ‘fake(s)’ of the painting and sells (or auctions)without disturbing the original.

Both theft and infr: He takes away the original and places a fake in its place so that no one notices for a few days (or maybe weeks)and he gets some breathing time.

Regards,

Hi…couldn’t resist the urge to reply.

I guess i have to clarify some of my points. For instance I said that the arguments about the difference between infringement and theft are esoteric in nature and the common pirating public will most probably remain aloof of the same. i guess Aditya agrees with me.

Secondly in your reply you start of by saying that you do not condone piracy or justify it.

however later on you seem to justify piracy on the ground that there aren’t enough plausible business models (like itunes) around and therefore “several people are FORCED to download songs illegally because buying a legal copy of the same is impossible”.

I beg to differ and i am sure that the Indian Music Industry (IMI), an Anti piracy group, agrees with me. In my interactions with the head of IMI it was very clear that there are enough CDs and DVDs available to provide for digital versions of songs.

As a colleague of mine would put it ” people are just damn too lazy to walk to the stores.”

Also even with Itunes, Apple had to conduct extensive negotiations and convince content publishers of the the DRM compliant AAC format before Itunes was made viable.

I believe that the convenience of a net connection does not give any body the right to pirate music.

Nobody is forced to pirate.Its just convenient to pirate of the net.

while it is obvious that one has to identify the problem correctly to find a solution, what does one do when the problem arises from the human aversion to spending money and the obvious draw towards convenience over conscience.

As far as those producers and bands that you have are concerned i wonder whether popularity transfers into profits. Id wish if you could provide one instance where a producer released movies for free on torrents hoping that the same will result in profits.

Hi Jacob. Thanks for your insightful replies. Sorry if my responses are a little delayed, but please continue posting your comments here.

I thought it would be better to try and engage in a discussion since we seem to have two very different perspectives.

You’re right. I did carve out an exception, but don’t you think it’s a valid one? I honestly am yet to find an online music store where I can pay with my credit/debit card to download just one song from an album. Why haven’t the Indian music labels tied up with a service where one can download a single track for Rs.10 instead of buying the CD for Rs.200? If such a service exists, I honestly don’t see a reason why people would pirate Bollywood music. And yes, it is convenient to pirate. But it would be equally ‘convenient’ to buy the music legally if it was available online. It takes the same number of clicks. The process is almost entirely the same, and I would argue that pirating brings in additional problems of viruses, the guilt associated with piracy, poor sound quality etc. I honestly, honestly believe that the Bollywood music industry and labels should look into this seriously. Don’t you think so?

And yes, you’re right. Some people are just too damn lazy to walk to the stores. But at the same time, you have to realise that a majority of Indians are very passsionate about their music and support their artists in any way possible. I remember a forum on Orkut that had more than 3,00,000 fans of A.R. Rahman, but every single time a new album was released, there was an obligatory post ‘ “Download from here to listen to the tracks, but please go out and buy the CD when it is available”. The responders were almost with exception, in full agreement.

You must understand that I come from a generation that has, for better or worse, been exposed to the piracy phenomenon and culture from a very young age. My views have been conditioned by debates on the present status/relevance of copyright law so they’re bound to differ from the views of those from an earlier time (I’m assuming you’re significantly older than me. Please correct me if I’m wrong and sorry! 🙂

I look at my dad’s humongous collection of expensive CD’s (ranging from Jazz and Blues to old Rock & Roll) and wonder if he would’ve still spent as much if he was born into this generation. But I am conviced that he would. Piracy is a problem because the music industry is resiting technological changes and the consequent impact on copyright law. This is why I call it ‘forced’. Don’t you agree that if they decide to adapt, the problem wouldn’t be so big?

(Continued)

I am glad you asked for an example of a movie where the producer released the film for free, expecting to make profits. Have you heard of the 2009 film ‘Sita Sings the Blues?’. Please refer to the Wiki page http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sita_Sings_the_Blues#Unorthodox_distribution . I’m convinced you will see the entire issue from a different perspective when a content creator (a ‘stakeholder’ as you call it) has this to say:

“There is the question of how I’ll get money from all this. My personal experience confirms audiences are generous and want to support artists. Surely there’s a way for this to happen without centrally controlling every transaction. The old business model of coercion and extortion is failing. New models are emerging, and I’m happy to be part of that. People have been making money in Free Software for years; it’s time for Free Culture to follow.” (from the website http://www.sitasingstheblues.com/)

Please don’t underestimate people’s desire to support artists. Do you really believe that there is a problem of “aversion to spending money” given the massive disposable incomes that 20-30 year olds in India are raking in these days? They surge on clothes, food and what not. Surely Rs.10 a track will be acceptable to them. Give them/us a chance. I’m curious to know what you make of my response.

Regards,

Amlan