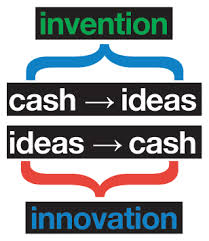

“If invention is a pebble tossed in the pond, innovation is the rippling effect that the pebble causes. Someone has to toss the pebble. That’s the inventor. Someone has to recognize the ripple will eventually become a wave. That’s the entrepreneur.

Entrepreneurs don’t stop at the water’s edge. They watch the ripples and spot the next big wave before it happens. And it’s the act of anticipating and riding that “next big wave” that drives the innovative nature in every entrepreneur.”

– Thus spoke Digital Entrepreneur Tom Grasty, in his blog here

That Russia has been a bulwark of immense scientific understanding and invention is no secret – history remains witness to the fact that Russian inventors have contributed more than generously to the ever expanding pool of global scientific thought – and yet, here we are in the 21st century, discussing the imbalanced investment priorities and innovation gaps in Russian policies despite its immense scientific capacity, availability of capital and rather well known desire to rise and rise.

A well educated population, adequate financial capital, a GDP that ranks in the world top ten and a simmering pool of brilliant scientific talent – we thought Russia had it all.

But for a country that is rich in assets and yet unable to quite make the mark so far as innovation is concerned, the presence of low innovation activity appears to point to an imbalance between available science and research databases, and innovative output production. There exists no doubt as to Russia’s extensive scientific knowledge – the question is as to its ability to effectively translate scientific products into economic development through its application in industries where the capacity to commercialize inventions exists.

An economy closed to private innovation and contribution

Russia’s economy is one that is essentially differently structured from countries in Europe or in the West, – while most countries have shifted their public expenditure allocation approach, reducing shares of energy and defence industry related research to and increasing the shares of medicine, biotechnology and intellectual property, Russia’s focus continues to lie primarily in mining and heavy metal industries, and gas and oil production companies – courtesy its dependence on the export of natural resources for the survival of its economy. The abundance of metal and oil in the country has led leaders to redirect and channelize massive portions public and private investment to this sector whilst compromising development in other important sectors of the economy – essentially favouring short term versus long term economic growth. Further, private sector funding and contribution to research and development projects in Russia is minimal– indicated by the fact that the weighted average of shares of state-owned enterprises in Russia’s top ten firms is 81% – providing a rather attractive space for bureaucracy, corruption and inefficiency to comfortably stretch out and settle in.

Russia lacks a market oriented research methodology adopted in the West that is directed at the establishment of high tech consumer goods industries – a sense of misplaced priorities has led to most science and tech-intensive industries in Russia to be pushed to achieve military modernization instead of domestic as well as international consumer product commercialization. As a result, and not surprisingly, researchers at main science and technology research organizations appear to be greatly disconnected from innovation activities translating into large scale commercialization, and they have little incentive to seek out the same within – this contributing to massive gaps in its innovation policy. While in developed countries every fourth national invention is patented abroad, in the Russian Federation only every sixtieth national invention is patented – 100 times less than in the USA and 50 times less than in Germany.

This issue is further amplified by Russia’s narrow and centralized R&D approach and financial strategy focused primarily on fields that the government arbitrarily deems important – without considering throwing the doors open to critique through consumer inputs or business consultations. In Russia, businesses are largely cut off from science and technology centres, creating a weak demand-supply chain from research institutions to businesses, as a result of which businesses are unable to use the investment in R&D to serve economic interests and create opportunities for public/private partnerships. There exists a imminent need to link Russia’s growing innovation structures to scientific research institutes to make the most optimum utilisation of available scientific knowledge through the translation of scientific breakthroughs into commercialized technological products.

“You want the milk without the cow!” (sic)

In his brilliant article, Loren Graham, Professor at MIT, recounts his experience on a visit to Russia, accompanied by colleagues.

“To Putin, like past Soviet and tsarist rulers, modernization means getting his hands on technologies but rejecting the economic and political principles that pushed these technologies elsewhere to commercial success. He wants the milk without the cow”.

Russia’s current laws do not embody sufficiently strong protections against violation of intellectual property rights. Russia is experiencing an epidemic of fake goods – as of 2011, Russia has a blooming market for counterfeit goods that some experts estimate to be worth between $3 billion and $6 billion per year – and this does not restrict itself to perfumes, clothes and food (including counterfeit meat products), but also alcohol, mineral water, audio and video CDs where Russia is an absolute leader in domestic counterfeit. Consumer Protection Service spokesman once commented, saying “it is difficult to prove that the counterfeiters broke the law” – highlighting the rather dismal extent of the problem in the country. What possible reason could anybody ever have to create, and sell in Russia when the odds of their creation being stolen are anything but minimal? Russia’s inability to take control of its out-of-proportion counterfeit market is perhaps a significant indication to innovators that they must think twice before deciding to create and sell internationally, especially when their interests are not being sufficiently protected domestically in the first place.

The Skolkovo Innovation Center, Russia’s flagship innovation project was established with the objective of encouraging development in science and technology, and awakening entrepreneurial spirit in innovators by aiding the growth of tech start-ups. However, considering that the Center is a USA and EU assisted development project, the sanctions imposed on Russia by both really lands the project in troubled waters – not that it was doing awfully well for itself otherwise, financially speaking. As Mr. Graham emphasises, what has managed to elude the country’s strategic plan for innovation and modernisation is the impending need to establish a socio-political atmosphere conducive to innovation, not against it – something that is currently absent in the state of affairs as they are today. Putin may claim to support the Skolkovo project, but when laws do not provide sufficient protection to the fruits of innovation, there is little impetus to create.

Technological innovation cannot be attained in a deleterious environment that fails to guarantee the freedoms and protections that characterise a ‘democratic’ nation, with laws that fail to uphold the ideals of free speech and liberty. Unfortunately, Russia has had a history of authoritarian regimes, and the existing state of democracy in Russia is, in many ways, quite an oxymoron – the current Russian government is only but a softer version of the dictatorial dominion under the Soviet rulers that came before Putin. His wildly unpopular censorship and information control policies, intolerance of criticism and law on treason clearly discourage the free and fearless expression of thought and opinion – a sine qua non for successful innovation.

A country that is as well endowed as Russia in terms of scientific genius is empowered to have any future it desires – if only the man at the helm of affairs offers the rights and protections necessary to achieve it. Until the country’s approach to innovation doesn’t undergo significant reformations, Russia’s abundance of scientific insight will continue to remain subdued and unexploited.