This two post series is an analysis of the case of IPRS v. Sanjay Dalia, recently decided by the Supreme Court of India. It dealt with the sticky question as to whether a plaintiff may sue in for Copyright or TM infringement in a jurisdiction when there exists another jurisdiction in which the plaintiff has an office and where a part or the whole of the cause of action arose. Part I analysed the application of the Heydon’s rule in this case, and this post now continues with that analysis. (Disclaimer: Long post follows!)

This two post series is an analysis of the case of IPRS v. Sanjay Dalia, recently decided by the Supreme Court of India. It dealt with the sticky question as to whether a plaintiff may sue in for Copyright or TM infringement in a jurisdiction when there exists another jurisdiction in which the plaintiff has an office and where a part or the whole of the cause of action arose. Part I analysed the application of the Heydon’s rule in this case, and this post now continues with that analysis. (Disclaimer: Long post follows!)

Is S.20 applicable in this case?

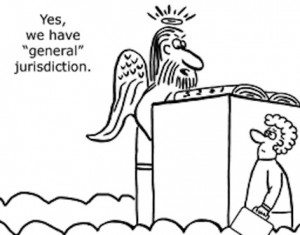

The controversy arises because in both Ss. 62 and 134 of the Copyright Act and the Trade Marks Act respectively, while conferring additional jurisdiction upon the courts where the plaintiffs are situated, the phrase, “notwithstanding anything contained in the Code of Civil Procedure” is used. The plaintiffs interpret this to mean a complete exclusion of the provisions of S.20 of the Code of Civil Procedure, meanwhile the defendants claim that certain provisions of S.20 can be applied depending on the facts.

The Explanation to S.20 of the Code of Civil Procedure that is causing all the problems here reads as follows,

“Explanation – A corporation shall be deemed to carry on business at its sole or principal office in 3[India] or, in respect of any cause of action arising at any place where it has also a subordinate office, at such place.”

Notice how this explanation is a deeming provision that actually identifies where a corporation can be sued and without this the provisions of Ss.62 and 134 that use the phrase, “carry on business” cannot be accurately interpreted. In such a scenario, this Explanation to S.20 becomes critical in interpreting Ss.62 and 134 and therefore cannot be excluded. The explanation also has the added advantage of using the phrase “corporation” that somewhat clarifies the more loosely worded phrase, “person” in the original section, to include companies registered under the Companies Act. It is therefore not appropriate to omit the Explanation to S.20 in any interpretative exercise concerning Ss.62 and 134.

How does S.20 interact with Ss.62 and 134?

In order to understand the exact mechanics of how S.20 interacts with Ss.62 and 134, it is important to recall two very important factors. First, the entity being sued is a corporation that has an office in a jurisdiction where the cause of action arose. It is also essential to remember that by the application of the Heydon’s rule (see Part I of this series) the remedies under Ss.62 and 134 are an additional remedy granted to allow plaintiffs, for the benefit of their convenience, to sue in areas where they have a presence.

Ss.62 and 134 are intrinsically linked to the jurisdiction where the cause of action takes place. In order to fully appreciate this, consider the three different jurisdictions that a potential plaintiff can sue for copyright or trademark infringement in:

- That of the defendants under S.20(a) and 20(b) of the CPC; or

- That of the plaintiffs under Ss.64 and 134; or

- That of the situs of the cause of action, either wholly or in part.

Option 1 is irrelevant to our analysis in the present case. The plaintiffs in this case have made use of option 2 in the present case, however due to the operation of the explanation under S.20 of the CPC, it effectively boils down to a suit under jurisdiction 3. This is because, as the court notes, the explanation to S.20 specifically notes that in case a corporation has a subordinate office in a jurisdiction where the cause of action arose it is to be sued there. If the interpretation as sought to be given by plaintiffs is to be adopted, the second part of the explanation to S.20 (after the disjunctive ‘or’) would be rendered otiose and merely the set of provisions (Ss.62, 134 and 20(a),(b) and (c)) would have been sufficient to convey that intention. In fact if such were the case, i.e. if the second part of the Explanation did not exist, then the interpretation as sought out by the plaintiffs might have succeeded. However, the second part of the explanation is imposing a restriction on this ability.

The Court also went on to distinguish the cases of Dhodha House and Exphar from the present case and noted that the questions presented in these cases were significantly different from the question presented in the one that they were dealing with. In Dhodha House, the suit was filed purely on the grounds that goods were being sold in a particular jurisdiction. The plaintiffs principal office was located elsewhere and it had no subordinate office in the jurisdiction where the cause of action arose, thereby taking it out of the scope of the second part to the explanation to S.20. In Exphar the question involved was more about the effect to be granted to S.62 as an additional remedy and did not concern itself with this particular question and the explanation to S.20.

This exercise of distinguishing these cases is extremely important to note as it implies that the court is speaking only to instances where the cause of action arises in a jurisdiction where the plaintiffs have a subordinate office and despite this, they choose to sue elsewhere. In scenarios where the cause of action arises in places where the plaintiffs have no office, or where there are multiple jurisdictions where causes of action arise, then this ruling would not be applicable.

The implications of this Decision

The implications of this decision are not very difficult to observe. For one, it disturbs the phenomenon of litigants suing in Delhi when the cause of action has arisen elsewhere. The practice prior to this decision was that in an infringement suit, where the cause of action arises in a jurisdiction outside Delhi plaintiffs prefer to sue in Delhi (sometimes even in a jurisdiction where the plaintiffs have their head office).

There is no denying that the Delhi Bar is considered best suited for IP enforcement or that the courts in Delhi have a far greater exposure to IP matters than most other courts in the country. It is also however not worth denying that this can be a tactic that is used to harass potential defendants, especially in situations where there is a disparity in the economic conditions between them. The court also took cognisance of this phenomenon and opines, “It was also submitted that as the bulk of litigation of such a nature is filed at Delhi and lawyers available at Delhi are having expertise in the matter, as such it would be convenient to the parties to contest the suit at Delhi. Such aspects are irrelevant for deciding the territorial jurisdiction. It is not the convenience of the lawyers or their expertise which makes out the territorial jurisdiction. Thus, the submission is unhesitatingly rejected.”

There are numerous instances of defendants, often poor business owners having to travel all the way to Delhi from the various corners of the country and having to employ a lawyer from the Delhi bar to fight their cases. The judgement however grants them only a limited relief in the instances where the cause of action has arisen in a place where the plaintiffs have a subordinate office.

Therefore, on a balanced consideration of all things, it is perhaps premature to judge whether this decision is actually going to help anyone.