A lot of people believe, albeit perhaps ignorantly, that the internet is effectively a Special Privileges Zone, where the rules of the “real world” do not apply – that it is a free-for-all space where everyone can take and post whatever they want, from whoever they want, without any consequences whatsoever. Far too often, writings have been picked up from x and shared by y as status updates on Facebook, without any attribution to the author, often reflecting the account owner’s intention to misrepresent the original author’s work as his own. Now effortlessly tickling funny-bones is no easy feat, mind you. At least once in all of your life, I bet you’ve found yourself in that awkward social situation where you just cracked that joke that you’d been practising all day – one whose end was met with little else apart from an uncomfortable silence and an awkward shrug or two.

That’s precisely why, when that comedian everybody loves or that friend who has always been the clown in class, effortlessly packs and brilliantly executes that perfect little joke – whether on stage or via his/her Twitter handle (in the mad pursuit of viral glory, of course), courtesy calls for you to refrain from sharing that joke with the world by representing it as your own creation.

Jokes require originality, must be credited.

Why? Because let’s face it – writing a joke isn’t much different from writing poetry, or a story even, for that matter. Coming up with witty two and four liners every other day requires the exercise of an ample amount of labour and skill – well, for at least most of the good ones. The element of originality, therefore, is inherent in an independent non-plagiarised joke. When plagiarism and copyright infringement are treated as such grave charges in the academic world, for instance, then considering how significant their original creations can be for stand-up comedians, why should jokes not be treated as intellectual property and subjected to the same copyright protections as other forms of art?

On the other hand, since absolutely forever, people have been stealing each other’s jokes. It is no secret that even comedians of the 21st century, and quite often than they’d like to admit, are joke-thieves – and perhaps in most of these cases, jokes aren’t reproduced verbatim – the idea forming the premise of the joke is the same, but the superficial elements are recycled before presenting it to the audience. One might argue here, that it is not so much the joke as it is the delivery system that matters, where comedy is concerned. However, accepting this would essentially mean that you’re okaying the fact that one person is trading off of the popularity of someone else’s joke and extracting value from it so as to add value to his/her own brand/image– and mind you, the act of “extracting value” could be done for something as simple as increasing your number of followers on Twitter. This, as you can guess, without bothering to acknowledge the source of your jokes, deceiving people into thinking “Oh, this guy’s hilarious” and calling their friends to tell them how they simply must check out the new funny guy in town’s Twitter handle. Chronic joke thieves – just because most people ignore your antics and the very question of ownership of content on social networking sites like Twitter, does not mean that such ownership doesn’t exist altogether.

Claiming that someone stole your joke, whether you shared it on the internet or otherwise, is a serious allegation in comedians’ circles – and proving this is a whole other ball game.

If the wording of two jokes aren’t exactly identical, how can you tell whether one was stolen?

The internet of course, has broadened the potential-copycat circle and also made it easier to point fingers, all at once. The numbers in your audience has gone from the couple of hundred people who’ve watched your shows to the hundreds of thousands of people who, thanks to social networking websites, don’t really have to get off the couch and buy a ticket to hear one of your rib-ticklers. Anybody on the internet has the option to surreptitiously lift one of your jokes, post it on Twitter and become a comedy star overnight. But then again, when you see your joke put up and shared by someone else as their own, isn’t it possible that you just turned out to be one of the dozen or more people that just happened to have independently created the same joke? Can’t two or three similar punchlines just all turn out to be one big, unhappy coincidence? As David Sims said, “Aiming for the lowest common denominator doesn’t equal plagiarism”.

This brilliant article on Splitsider, whilst mentioning a number of instances of clashes between famous comedians in the your joke-my joke battle, reads – I think it’s also possible that every human being has coded within his DNA a basic, natural progression of humor, and that because all comedians follow this instinct, it’s fairly common for two comedians who have the same initial idea to take a joke in the exact same direction.………….doesn’t it seem possible that two isolated comedians who start with the same, basic truth could each stumble upon a single image that perfectly illustrates that truth?

It seems to me that one, two, three and even four liners are far more likely to have been “independently stumbled upon” by multiple comedians at once, rather than jokes that more descriptive narratives, taking a while before the punchline finally arrives. Either way, to claim copyright infringement, the first question to be asked is – is the joke so splendidly original, that it contains elements that is unlike anything that anybody in the comedy circles has ever dreamt up before? If the answer to this is in the affirmative, then it makes for a strong case of copyright infringement. In other cases, where we’re talking about jokes that are so visible and obvious that anybody could have come up with it, the task of proving infringement becomes a much harder one.

The law in the UK holds that a joke told by a comedian before a live audience cannot be copyrighted unless it has been recorded in writing or otherwise, beforehand. Which brings me to my next point – where jokes are lifted verbatim (here I speak of the splendidly original kind), plagiarism is most often than not, clear, and there could lie a case for copyright infringement. However, in other cases, where only the premise or idea that forms the basis of the joke has been lifted and the joke itself, has been differently retold, the way forward remains unclear. Could this then amount to a derivative use of the work – a right exclusively falling within the ambit of those conferred upon the copyright-holder – effectively constituting copyright infringement?

Speaking Twitter-wise

A 2008 article on Techdirt laments, “It’s unfortunate that we’re now reaching the point that something that used to be a shared experience is also going down the path to being protected and limited”. Why, pray? There are people whose entire professional careers depend upon the funny anecdotes they write – must they be forced to ignore instances of joke theft because, well, sharing is good?

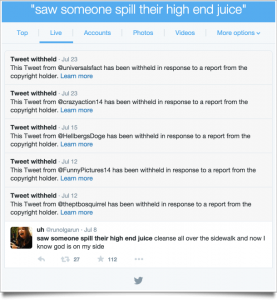

Freelance writer Olga Lexell, for instance, wrote to Twitter when she saw her one-liner being re-tweeted thousands of times over, without any credit whatsoever – I simply explained to Twitter that as a freelance writer I make my living writing jokes (and I use some of my tweets to test out jokes in my other writing). I then explained that as such, the jokes are my intellectual property, and that the users in question did not have my permission to repost them without giving me credit. Twitter’s crackdown on legitimate complaints of copyright infringing tweets is no different from what Youtube, for instance, has been doing to deal with similar complaints against videos – and I find it perfectly legitimate because atleast on the face of it, it seems clear that she is in fact, the very source of the joke. Users have cared little about acknowledging Lexell as the real author – who again, makes a living out of writing what she does- and she can’t make them, so she’s using Twitter’s mechanism to address copyright grievances to take down what is, leaving the whether-copying-on-Twitter-is-okay debate aside, legally speaking, copyright infringement.

If this was not a Twitter war, but a poetry blog war, where one user has picked up a one liner from somebody else’s blog and put it up on his own without according due credit, any uproar over copyright infringement by an author of the original writing would have been seen as appropriate and necessary, with status updates and tweets circulating all over expressing disgust over “my, what the world has come to today”. What then, renders tweeters ineligible to do just the same? Is Lexell really being unreasonable?

The issue here is one that, I believe, could easily be resolved if only people would just abide by commonly accepted and recognized social norms. You know you didn’t write that – instead of falsely representing the writing as your own creation, just credit the source, and you’re good to go! How hard can that possibly be? The issue becomes 5x worse when comedians use plagiarised jokes during live performances. I’m not advocating the odd-seeming idea that comedians must now begin requesting other comedians for a license to use their joke – common courtesy, again, is all that must be paid regard to, and I think Twitter’s takedown policy might push people to do just that.

It’s going to be fascinating to see how the law works its way through this little brain teaser.

Hey Kiran,

Overall a really nice article and a very good read, but I do feel that you’ve missed an essential angle to the story, and that is the counter view that exists in a lot of IP scholarship about “Negative Spaces”. Negative spaces is the argument that there are these different industries ( Fashion, Tatoos, Recipes, Stand up Comedy) in which norms have been developed by the people in the industry that have served as a viable and in some cases a better alternative to an IP protection. What does this mean in tangible terms? This means that the norms of the stand up comedy community or of the tatoo community dictates that you represent each other’s work. Therefore, the idea being that the big players would never dare to be ostracised or ex-communicated from this inner ring of confidence that they all share. In fact, in the stand up circle, there has been a much greater reduction of these forms of joke plagarisms that you allege for a long time, that it has almost become minimal ( Chris Sprigman and Dotan Oliar, “There’s No Free Laugh (Anymore): The Emergence of Intellectual Property Norms and the Transformation of Stand-Up Comedy,” 94 Va. L. Rev. 1787 (2008).)

Agreeably, twitter is a whole other ball game where individuals do not owe each other the same level of obligations as my inner circle argument, but honestly that is at a minimal level.

I feel that a counter analysis on whether stand up needs IP and the argument that it doesn’t and atleast facing that critique would have made this a more balanced article to read.

That aside, I thoroughly enjoy the topics you choose to write about, so keep writing!

Thanks and Regards

Harshavardhan