In a path-breaking development for Indian trademark law, the Supreme Court reiterated yesterday that IP rights are “territorial” and not “global”. The court was deciding a matter involving “Prius”, the brand under which Toyota sells its leading “hybrid” car.

The court held that merely because Prius is well known outside India does not mean that it enjoys a “reputation” in India as well. That has to be independently established!

The court’s decision is a delight to read, not least because of its lucidity. However, I have a few issues (minor ones) with some jurisprudential aspects of the ruling.

Fortunately, this is one of those rare IP cases, which managed to swim past the “interim” stage. Indeed, this dispute filed way back in 2009 underwent a full length trial before it made its way to the Supreme Court.

Facts of the Case

Briefly, the facts of the case (Toyota Jidosha Kabushiki Kaisha v. M/S Prius Auto Industries Limited) are as below:

The Plaintiff (Toyota Jidosha Kabushiki Kaisha) sought to prevent the Defendants (spare parts suppliers) from using the trademarks “Toyota”, “Innova” and “Prius”. The first two marks were registered trademarks of the Plaintiff and the lower courts had no difficulty in finding in favour of Toyota on this count. The Defendants did not contest these findings before the Supreme Court.

The contest was only with respect to the trademark “PRIUS”, which the plaintiff claimed belonged exclusively to it. Interestingly, the plaintiff had no trademark registration for this mark, but the Defendant did (a registration dating back to 2002).

Toyota contested this registration by the defendants, claiming that it was the first user of Prius (and began using this mark as early as 1997) and that the Defendants had wrongly and dishonestly registered the same in India.

As such, the only question before the Supreme court was: Despite the defendants’ registration of Prius as a trademark, could the plaintiff still claim that they have a stronger (passing off) claim to the said mark, being prior adopters/users of the same?

Interestingly, this case did several earlier rounds before the lower courts, and underwent a full fledged trial before it made its way to the Supreme Court. Our previous posts on this case can be found here, here and here.

Ruling of the Court

The court ruled in favour of the Defendants, noting that the Plaintiff had not supplied enough proof of its “reputation” in the Indian market. In other words, although trans-border reputation was now very much a part of Indian law (ever since the Whirlpool decision), such reputation could not merely be asserted, but must be proved. And within the “territory” of India. The court notes:

“…if the territoriality principle is to govern the matter, and we have already held it should, there must be adequate evidence to show that the plaintiff had acquired a substantial goodwill for its car under the brand name ‘Prius’ in the Indian market also..”

In other words, although the mark may be very well known abroad, that by itself is not sufficient. Reputation in the local milieu must be proved as well. The court noted that in the year 2001(which, as per the Plaintiff, was the effective date on which a significant cross section of Indian consumers would have known of their mark), the Internet was still not in widespread use and therefore not many would have learnt of the mark:

“The advertisements in automobile magazines, international business magazines; availability of data in information-disseminating portals like Wikipedia and online Britannica dictionary and the information on the internet, even if accepted, will not be a safe basis to hold the existence of the necessary goodwill and reputation of the product in the Indian market at the relevant point of time, particularly having regard to the limited online exposure at that point of time, i.e., in the year 2001.”

Further, the mere appearance of the mark in the context of news stories would not suffice. “The news items relating to the launching of the product in Japan isolatedly and singularly in the Economic Times (Issues dated 27.03.1997 and 15.12.1997) also do not firmly establish the acquisition and existence of goodwill and reputation of the brand name in the Indian market.”

The court therefore ruled as below:

“All these should lead to us to eventually agree with the conclusion of the Division Bench of the High Court that the brand name of the car Prius had not acquired the degree of goodwill, reputation and the market or popularity in the Indian market so as to vest in the plaintiff the necessary attributes of the right of a prior user so as to successfully maintain an action of passing off even against the registered owner.”

Analysis: A Pushback against TM Expansionism?

The court’s ruling appears robust and well reasoned. Given the undue expansion of IP rights in the recent past and a shift away from the “consumer confusion” model to an unrestrained ability to control any and all third party uses of the mark (whether or not the consumer was confused), this ruling by the apex court will serve to bring the balance a bit back. And take trademark law back to its foundational roots; by blunting the pervasive overreach of the trans-border reputation doctrine.

Two important points on the courts’ jurisprudence worth noting:

i) The court appears to lean towards the view that mere reputation alone would not suffice for a passing off action. Rather, one must also demonstrate local “goodwill”, which at the bare minimum means that there must be some “customers” within the local jurisdiction. The court relies on foreign precedent for this, particularly an English decision(Starbucks British Sky Broadcasting ).

However, while the court states this in the former part of its order, it does not appear to follow through. In the latter part of the order, it appears to suggest that mere cross border reputation would suffice, and one need not insist additionally on goodwill as well.

ii) Interestingly, the Delhi High Court division bench had ruled that at the trial stage (when the action is not an interim quia timet one), it wasn’t enough to merely prove “likelihood of confusion”. Rather, given that the defendant would have used the mark for a sufficient number of years by then, one had to prove actual confusion. However, the apex court disagreed with this proposition and sided with Toyota. It ruled proof of actual confusion is often difficult to adduce. Therefore likelihood of confusion was the appropriate test, even at the interim stage:

“Proof of actual confusion…. would require the claimant to bring before the Court evidence which may not be easily forthcoming and directly available to the claimant. The onus of bringing such proof, as an invariable requirement, would be to cast on the claimant an onerous burden which may not be justified.”

I’m not sure I agree with this fully. If a sufficient period of time has lapsed since the time of first use of the allegedly infringing mark by the defendant, wouldn’t the non-procurement of evidence (of actual confusion) mean that there was no likelihood of confusion in the first place? Unless I’ve got my sense of logic horribly wrong.

Other Aspects of the Courts Ruling

i) The court refused to wade into the argument of whether or not the defendants were honest or dishonest in adopting the mark Prius. The Defendant’s story on this count is a rather interesting one.

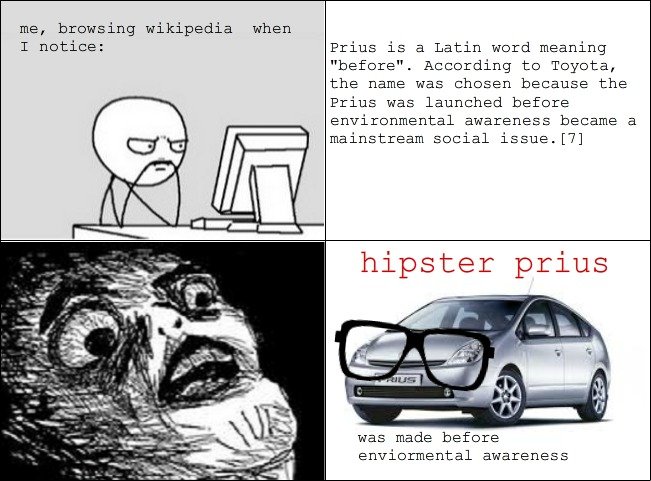

The defendants claimed that they were pioneers in the field of manufacture of Add-on Chrome Plated Accessories. As such, they searched high and low for an appropriate term that could describe their first attempt (or “Pehla Prayas” in Hindi). After extensive research, they finally found the word “PRIUS” in the dictionary (a Latin term meaning “to come first”) which they picked up and used.

Sure: this is the land of Yoga, but that is one hell of a stretch!

In any case, the alleged dishonest adoption did not matter to the apex courts’ ultimate analysis. It correctly noted that even if the Defendants had been dishonest, that by itself would not exonerate the Plaintiff of having to prove that they had trademark rights in “Prius” in the first place.

ii) Secondly, the court noted that Plaintiff delayed taking action against the Defendants: “We cannot help but also to observe that in the present case the plaintiff’s delayed approach to the Courts has remained unexplained. Such delay cannot be allowed to work to the prejudice of the defendants who had kept on using its registered mark to market its goods during the inordinately long period of silence maintained by the plaintiff.”

iii) Thirdly, the court also appears to have completely overlooked the contention of the Plaintiff that “Prius” was a well known mark in India. No doubt, it is a tad bit illogical to contend that a mark is well known in India, when it is otherwise found to have no significant “reputation” in the country. However, given the not so clear provisions governing well known marks in India, could one argue that a mark is “well known” in India, despite lacking the necessary local “reputation”/”goodwill” for the purpose of a passing off action?

Conclusion: Legal Legibility

All in all, a very refreshing read from the Supreme Court. Lucid, not too lengthy, and very well reasoned. So on legal legibility (a point I’ve often ranted about in the past), I’d rate this decision quite highly. And on its jurisprudential rigour too. Though on certain legal aspects (such as whether or not a passing off action requires proof of local “goodwill”, and not merely local “reputation”), the decision could have done far better.

ps: I want to specially thank Pankhuri for her timely help with this post.

pps: Image from here.

Thanks Shamnad for writing pointedly, as always, about this. I agree entirely with the gaps you’ve identified in the Supreme Court’s decision. However, having had some time to let the decision settle, I find that these gaps are far more troubling than may initially be apparent.

On territoriality, it’s pretty clear that this Court does a disservice to the vibrant debate around the requisites for establishing goodwill in different jurisdictions. Its conclusion that “the overwhelming judicial and academic opinion all over the globe” is in favour of territoriality is not just demonstrably false but isn’t even in line with the UKSC opinion in BSkyB – on which this very Court so heavily relies – which goes to great lengths to show that this is, in fact, heavily contested ground.

More than that, though, this Court’s conclusion that the Claimant must demonstrate “adequate evidence” of “substantial goodwill” in India is extremely vague. It may be intuitive to endorse it in this case because the outcome itself is an intuitively agreeable one but that’s a dangerous peg on which to support extremely loose framing of this nature. Inconsistent appreciation of prior use evidence is a sizeable problem, and this Court does little to fix this problem.

Further, as you’ve hinted, this Court leaves the judicial assessment of goodwill in passing off claims at a genuine crossroads. Taken at its full meaning, I struggle to see how it’s possible to simultaneously endorse this Court’s position, while also holding the view that international/cross-border reputation can be used to set up passing off claims in India. It throws the continued relevance of decisions like Whirlpool and Milmet Oftho and several others into considerable doubt, and it’s particularly jarring that this Court was evidently aware of the international reputation line of cases but chose not to engage with them.

On likelihood of confusion vs proof of actual confusion, the Court suggests that likelihood of confusion is a fairer standard to hold Claimants to than proof of actual confusion. In itself, this is fine, if it is indeed for the reason that actual confusion is harder to prove. However, the Court also says that likelihood of confusion is preferable (a) because requiring actual proof would inevitably mean resting that burden on the Claimant and (b) because likelihood of confusion “would be a surer and better test” of proving a passing off action. There’s absolutely no reason to believe either is true.

Finally, on the framing of the question itself, I think it’s amply clear that the conclusion by this Court is simply to the effect that, since the Claimant’s goodwill in India is insufficiently established, nothing survives for adjudication. This is critical because it means that the Claimant’s case has been rejected at the threshold, and that the Defendants’ case on merits (their own questionable etymology story, the delay/acquiescence in bringing the action itself, and so on) is totally irrelevant. Again, I’m hard-pressed to find an outright defence to a post-trial finding of this nature.

Thanks for your incisive comments Eashan! Would love it if you can write this up as a more comprehensive critique of the judgment. I agree with you on most points. Save the last one on dishonest adoption. Even if the adoption were dishonest, will it impact the outcome of the case. Given that the plaintiffs had failed to establish their trademark rights in the word in the first place (as of the relevant date)? I’m asking since your last line appears to suggest that such a post trial finding is not defensible. Unless I’ve misunderstood? Thanks and please do consider writing up these thoughtful points as a guest post.