We move into the last few entries to our Fellowship applicant series with this post by Thomas J. Vallianeth, a third year student at NLU-Jodhpur. In this post he takes us through the copyright implications of what is perhaps one of the biggest technological advances we’ve made in the last decade – 3D printing.

3D Printing and Indian Copyright Law

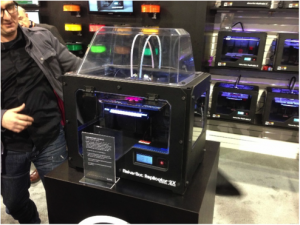

Hailed as the next best thing to happen to the printing industry since the invention of the printing press itself, 3D printing is no doubt creating ripples around the world. Since the last post here, the technology has advanced in leaps and bounds. Maker Bot, now sells a printer which enables people to “print” a number of objects at home. The Royal Air Force recently flew a plane that had components made by 3D printing. While functional, industrial components have been generated by this process for a long period of time now, the designs that have been replicated have become increasingly complex and it is only a matter of time before it becomes as common as conventionally printing on paper. 3D scanners which allow people to scan 3D objects have now become increasingly portable and it won’t be long before they are as commonly available and as commonly used as cameras.

However, as during the nascent stages of most reproduction or transfer technology (like the Betamax or Napster), intellectual property laws have taken time and a fair amount of deliberation to cope with such rapid advances in technology. This post seeks to examine whether the Indian copyright regime is adequate to deal with this technology.

What is 3D printing?

A 3D printer essentially operates by means of a “design” (usually called a computer aided design or a “CAD file”) that is created by specialised software or by means of 3D scanners. The printer then prints or moulds this design layer by layer onto specialised raw materials, usually forms of plastic. Think of it as similar to printing on paper with an added dimension.

Copyrightability

The entire process of 3D printing as described above includes elements in which copyright may persist. These are: the CAD file and the “printed” object itself.

The CAD file: A CAD file will generally be protected by copyright as an artistic work, provided the EBC standard of a minimum creativity is demonstrated. However the situation is quite different when the CAD file is generated by scanning an object. In this case the file will ultimately reflect the characteristics of the object being scanned and therefore would not satisfy this standard. The real copyright in this case vests in the object and not the file.

Although the computer file is called a design, it doesn’t fit the legal definition of a design in all cases. S. 2(d) of the Designs Act of 2000 requires that the visual features be applied by an industrial process. The phrase “industrial process” has been interpreted by courts to imply a process carried out on a large scale. Most 3D printing that exists today (which is used mainly for manufacturing) might fit that definition. However, with the advent of portable 3D printers into homes and office spaces, the CAD files used do not fit the definition of designs as per the Act as no large scale application is involved. The solution to this dissonance would probably be to revert to copyright protection as it persists in artistic drawings, on which the designs are based (Microfibres v. Giridhar).

The “printed” object: Only the visual features, as severed from the functional part of the printed object can be subject to copyright protection. Therefore, if for instance there is an intricate pattern in a 3D printed chair, only that pattern would be protected, not the chair itself. Plastic moulding as a concept has been in use for a number of years now and courts have not been reluctant to hold that provided other requirements of originality were met, the visual elements of these objects were subject to protection (See for example Escorts Construction Equipment Limited v. Action Construction Equipment Private Limited and the 10th Circuit’s opinion in Meshwerks, Inc. v. Toyota Motor Sales).

Infringement

Infringement in the context of 3D printing would be governed by Section 14(c) (i) of The Indian Copyright Act, 1957. It states that the conversion of a three dimensional work into 2D form and vice versa would be the exclusive right of the author of the artistic work. Therefore, the action of scanning a copyrightable object would appear to be an infringement of the author’s exclusive right to convert it into a two dimensional form. Similarly, considering that copyright persists in the CAD file itself, its 3D print itself might therefore amount to infringement of the author’s copyright over this file. There are numerous services (like Thingiverse and Shapeways) that offer CAD files that people may buy and print in their homes, but they usually operate under a creative commons license, which relies heavily on the consent of the author, but this is not always easily available. It appears therefore, that in order make this technology truly portable, a regime of licensing needs to be developed that can overcome this barrier (an iTunes model perhaps?).

Industrial use of 3D printing, as I had mentioned earlier has been in practice for a while now and the recent amendment to the Copyright Act in 2012 in S. 52(1) (w) allowed for an exception for the making of the purely functional parts of an artistic design.

In conclusion, it appears that our copyright law has, at least in principle, accounted for most aspects of 3D printing. However, the problems regarding licensing are to be resolved.

Thanks Swaraj for detailing on the current status !!! Hoping you will get a chance to update at a later point. Thanks Again.

Thanks for the interesting post!