A few weeks ago, the Centre for Internet and Society and the Observer Research Foundation organized a conference focusing on “Freedom of Expression in a Digital Age” in association with the Internet Policy Observatory of the Center for Global Communication Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. For their panel on “Balancing Freedom of Expression and other digital rights”, I was invited to discuss Copyrights in this context. While I wasn’t able to make it to the Conference, I did send in a written piece which will be included in their upcoming outcome document publication. In the piece, reproduced below, I take a broad overview at the role copyright plays in the digital world vis-a-vis freedom of speech. For the sake of brevity, I’ve glossed over some nuance – or it would’ve required a much longer piece – however I hope the thrust and spirit of the piece is carried over nonetheless.

(More details on the overall conference are available here).

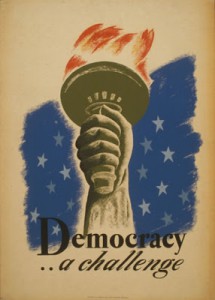

“King Copyright” has no place in a Democracy

The rise of draconian copyright policies, world over, has given rise to a growing conflict between copyright law and the right to freedom of expression, with the global push for the expansion of copyright laws leading to copyright policy often being unbalanced as well as unnecessarily obstructive to the freedom of expression. This is quite unfortunate, as while there is certainly an inherent tension between copyright (which prevents copying of expressions), and the freedom of expression, the two are not necessarily incompatible. To expand on this, copyright law is about incentivizing and rewarding the creation and expression of ideas, while the right to freedom of expression ensures there is a market place of ideas. In their relationship with each other, copyright law trades off certain temporary and limited restrictions on expression, for the sole purpose of ensuring there is more expression generated. If anything, these two concepts seem to be complementary. However, as the world around us tells us today, the above sentence needs to be modified, for it is only a balanced copyright system that is about incentivizing and rewarding creators, and it is a balanced copyright system which is complementary to the freedom of expression.

Given that copyright is a complex bundle of rights, there is the need to specify, that when we talk about the conflict between copyright and freedom of expression, we are referring to the set of economic rights given by copyright, such as the exclusive right to reproduce the copyrighted work, prepare derivative works, distribute copies, public performance rights, etc. We are not referring to ‘moral rights’, such as the right of integrity of work, right to attribution, etc. This distinction is important, as claims to maximize (economic) copyright laws, are often buttressed with moral-rights laced rhetoric, thus building the straw-man argument that maximizing copyright is required to benefit the creator. However, as the history of copyright clearly shows, these economic rights have primarily benefited intermediaries between the creator and her audience – intermediaries that used to be necessary for the creator to get a platform that allowed her to get access to an audience. These included record labels, publishers, movie houses, etc., i.e., entities that had the capital, power and ability to select, market and present creative work to a larger audience. Often times, these entities also provided the capital required even to create a work.

However, with the advent of the digital age, the cost and effort in reaching a larger audience has been slashed dramatically. A variety of online intermediaries are now available for cheap, if not free, and also unlike traditional intermediaries, are also often agnostic (and thus not picky) as to the type of content they host. This means the cost and effort of creation, production, and distribution have all been slashed. In parallel, access to massive quantities of content along with accessible tools of creation and distribution, have blurred the lines between consumers and creators – leading to a more dynamic and vivid ‘marketplace of ideas’ being generated. Further, the “Openness” movements in the digital space have all contributed towards a partial move away from a ‘proprietary’ approach to revenue generation models and to marketing and distribution of content.

The digital world has given rise to previously unimaginable quantities of creative work being generated on a daily basis, and in the process, leaves its relationship with copyright as one that needs to be re-examined. As a fundamental matter, the financial incentives that traditional copyright laws premised as necessary and hence provided through mechanisms of control, have a much-reduced role in the digital age where the notions of ‘free’, both in terms of cost as well as control, have significant influence.

At the same time, all these developments have greatly changed, as well as reduced the roles and powers of the traditional intermediaries in the content ecosystem. The fear of being removed from their seat of power has pushed these traditional intermediaries, i.e.,“Big Media” into lobbying strongly for more stringent copyright laws, trying to maximize control over content – leading to two types of problems. These are: Abusive policies such as region locked content, dictating types of usage that purchased content can undergo, continually lengthening copyright durations, reducing the scope of fair use, ‘three strike’ rules, etc., which have gone far beyond what a ‘balanced’ copyright system should foster; and abusive enforcement mechanisms, such as blanket takedowns, (threats of) expensive litigation proceedings, erosion of due process laws, expanded criminal penalties, etc.

Together, these have led to ridiculous as well as class-ist situations, such as ‘amateur’ creative content facing the continual threat of cease-and-desist notices from big media houses who have the power and money to keep sending out frivolous claims; chilling effects on free speech due to fear of copyright infringement proceedings; quick settlements made by small party recipients of such notices out of fear of long and expensive litigation; aggressive litigations being made even on academic work in developing countries where access to scholarly material is already very inaccessible, despite fair use provisions which ought to allow it, etc. It’s very clear that the abusive power of copyright is being explored in worrying depth.

Aside from the ‘inherent’ abusive potential of maximalist copyright policies, there is also the fact that copyright law, which comes with the advantage of having easily called upon rhetorical justification, (e.g., we must stop piracy at all costs!) can also easily be used to censor speech. With the digital world giving rise to a multitude of new voices and perspectives, governments world over are suddenly facing much more vocal debate and opposition on a varying number of issues. The instantaneous nature of communication over the internet has led to an ability to exchange and collaborate ideas and information like never before.

Free speech and expression in the digital world moves from simply being a democratic process, to being an active part of promoting a democratic culture. As Jack Balkin notes, the power of freedom of expression, which concerns the individual’s ability to participate in the production and distribution of culture, is greatly amplified in the digital age, where technological mechanisms greatly expand the possibility of realization of a truly democratic culture. At the same time, the same technologies that make this possible are also subject to control and infrastructural design limitations – and this has not been lost on governments and big corporate houses which are looking to gain control over this new digital territory — and this is where a maximalist copyright policy agenda is currently trying to set foot in. It’s no coincidence that insidious attempts at standardizing such problematic copyright policies world over have been made through greatly protested secretive draft multinational agreements such as the “Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement” (ACTA) and the “Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement” (TPP).

Given where we are currently, there must be a renewed movement at acknowledging that copyright law is no sacrosanct end in itself, but rather exists to encourage the generation of creative content. And if this is to be achieved, the growing conflict between free speech and copyright must not only be acknowledged, but the subservient role of copyright to the democratic purposes of free speech must be emphasized.

This is an argument I don’t wish to enter into (though I hope industry interests were also represented in that conference) but there’s another aspect to the whole question that is getting overlooked. This is eloquently argued by Jaron Lanier in “Who Owns the Future?”. The point made is that the internet hugely enriches a few intermediaries–Social Networking Sites, Search Engines or other intermediaries, and the like, who benefit from both the uncopyrighted data and works (including personal photographs etc.) and performances uploaded or accessed by ordinary people and that this is affecting both employment of millions of people. This is contributing to the growing social and economic inequality in developed countries. Laws that obligate the automatic flow of some revenue to those who create it are feasible. Read the book and think about it.

That’s actually a book I’ve been meaning to read. Thanks for suggesting it again, I’ll get around to reading it sooner rather than later hopefully. I don’t want to comment on the point till I’ve understood how it’s being made exactly; but thanks for leaving it here to ponder over.